- Home

- Velibor Colic

The Uncannily Strange and Brief Life of Amedeo Modigliani Page 5

The Uncannily Strange and Brief Life of Amedeo Modigliani Read online

Page 5

VENI CREATOR SPIRITUS, says the drunken Cocteau, dancing round the fire a ritual, fancy-dress, arrhythmic negro dance.

VENI CREATOR SPIRITUS, yells the drunken Cocteau, falling onto his knees, panting like a steam engine, broken, haggard, discarded like orange peel.

Four days before his death Amedeo Modigliani sees the burned paper forming a fine, pale, almost white powder of ash. He sees the smoke becoming a dove with a ring on its right leg bearing Gog and Magog, monsters that will appear on Judgment Day.

MY GOD, thinks Modigliani, this man is burning Dante. And, breathless, panting (we should not forget that he has been breathing through gills like a fish for two weeks now), he approaches the crushed Cocteau and places his hand on his shoulder.

HELLO, BIRD, says Cocteau, without raising his head.

Cocteau, Explanation

IN THE ROTONDE, Cocteau, relatively sober by now, explains to Amedeo that he burned Dante for the benefit of literature. Mon ami, he says, after Dante all our efforts in the field of literature become pointlessly comic and stupid.

And anything that makes human efforts pointless, comic or stupid deserves to be burned, doesn’t it?

Amedeo, Soutine

PEOPLE ARE EITHER far away or they are not there at all, says Chaim Soutine that same afternoon to Amedeo, visibly moved as he supports the weight and the large, noble head of the Jew, the vagabond, the painter and sculptor Amedeo Modigliani.

Moved, he adjusts his deep, healthy breathing of a mature man to the feeble, grinding rasp of the sick man, still almost a boy.

On the pavement we see just one shadow.

The bigger, longer one.

On the pavement, as the two of them stagger, we observe, already predestined for destruction, the first shy, premature mark of the spring that will not come.

They are half-dead, trodden primroses, yellow and foolish as girlish modesty. On the pavement we notice wine vinegar, and the vomited sperm of dark-skinned Arab boys, we notice sharp stones, and the knives of lusty soldiers.

On the pavement we notice also a Pierrot with a hurdy-gurdy, an angel with a sword, and other such creatures as sleep by day and live by night.

On the pavement we notice the pavement.

People are either far away or they are not there at all, says Chaim Soutine, swearing forcefully, manfully, towards the town gates.

Amedeo, Port

AT HALF PAST TWO in the morning, not by chance, because that is the time when a poet dies every day, two friends see, astonished, A GREAT PORT.

They see large, WHITE SHIPS.

Anchored and sluggish.

CARA ITALIA, Amedeo Modigliani is the first to react, running, his arms wide in the shape of a fan, like a crane’s wings.

Chaim Soutine stands, in amazement, looking at the miracle.

CARA ITALIA, Amedeo Modigliani trembles and kneels, like some Flying Dutchman, without dry land, homeland or grave.

The boats are sluggish, asleep and silent.

Just like Divine mercy.

Evening, Hunger

ON THE TWENTY-FIRST OF JANUARY 1920 AD, wearing his Maltese Cross round his neck, Amedeo Modigliani, completely mad and hungry, hugs and kisses his wife Jeanne Hébuterne, sewing up her mouth, vagina and eyes with the silken threads of his enriched, consumptive saliva.

Many years later, Leopold Zborowski would talk about his drinking bouts lasting several days, and about one of Jeanne’s festive dinners, when Amedeo Modigliani, quite overcome with joy and wine, picked up a hunting rifle and shot a wandering angel off the roof of a church. It was subsequently found to be nothing other than sea foam and feathers.

Grasshoppers from Algiers, the muzzles of smiling lions, a wash board, woodlice, tarot cards, the left ear of a Chinese mandarin, frozen boxes, a neon Madonna, tart grapes, drunken vanilla, barley shoots, an Austrian eagle, camels’ blisters, space dust, little boys’ testicles, tasteless bananas, artists’ paints, dead fish from the Seine, big-eyed crabs, well-endowed monkeys and, of course, the salted tail of a young pheasant.

The menu, in other words, was as festive as it was strange.

The mood of the guests listed below was on a very enviable level:

Chaim Soutine, Leopold and Hanka Zborowski, Nekrasov, Baronness Béatrice, the Archangel Gabriel, Donna Clara the landlady, Sebastian—the one year-old son of the unfortunate Madame Carmelita, Max Jacob, Cocteau, Lolotte and Jeanne Hébuterne, tipsy brunette and hostess.

The thirteenth, at the head of the table, was Amedeo Modigliani, who in the first hours of morning, on the second day, quite overcome with joy and wine, fired a hunting rifle.

Any similarity with DA VINCI’S LAST SUPPER is unintentional and fortuitous, announced Leopold Zborowski finally.

Towns, Tears

I SEE A MILLION light-bearing towns, said Amedeo Modigliani tipsily, accompanying his guests to the door, I see Rome, the Pope’s capital, I see Madrid, city of bulls and poets, I see drunken Moscow, I see large ships spreading their sails in Barcelona, I see the shots fired by Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo in 1914, I see the burning eyes of virgins in Naples, I see syphilitics waltzing in Vienna, I see a flaming field of poppies in my native Livorno, I see a bare, ugly hill in Jerusalem, I see crazy hatters in London, I see a fly and a spider dancing a tango in Buenos Aires, I see death as a regular phenomenon in Santiago, I see avenues of mighty bearded trees in Budapest, I see aggressive negro music in the docks of New York, I see Whitman’s lilac in Washington, I see women swimming in Avignon, I see a young moon with its belly turned towards sleeping Granada, I see fat German rabble drunkenly whooping in the streets of Munich, I see saints, cows and firecrackers in Bombay, I see a crowd of minarets against the sky above Istanbul, I see the sleeping roofs of Prague by night, I see the sweaty rifles of the Bolsheviks on the white face of Saint Petersburg, I see the walls of the Bastille, I see a mustachioed sergeant in Berlin yelling ‘SIEG HEIL’, his throat slit, I see all the President’s men in the centre of Havana, I see twenty-three drunken carpet-makers in front of the gates of Katmandu, I see juicy women’s breasts in Hamburg windows, I see the great babbling tongues of plump café owners from Lyon, I see the bird of the south in Palermo, I see lovers from Verona, I see a heap of rat-like faces in the sewage system of Copenhagen, I see unreasonable delight on the faces of peasants on Saint Valentine’s Day in Caracas, I see Chicago, and I see:

I SEE THAT THE ENTIRE WORLD IS PARIS.

AND I AM ABOUT TO LEAVE IT.

GOODNIGHT TO YOU, CAMARADES.

A VERY GOODNIGHT.

The people leave, turning up their collars, blowing on their fingers, coughing, in the almost grave-like silence. GOODNIGHT BIRD, says Cocteau, who is the last to leave, carrying a litre of wine and some unfinished poems in his pocket. And, leaning on the doorpost, Amedeo Modigliani, the cursed painter from Livorno, stands, shivering with cold, but says nothing.

He is silent.

And his silence seems to explain everything.

Amedeo, Death

WHO KILLED THE CRANES, mutters Amedeo Modigliani who has just woken up. He shivers as he inserts his narrow, pointed little Jewish backside into his frayed trousers, unstitched in places, the pockets filled with unpainted faces, unspent coins and as yet un-sniffed cocaine.

Cranes, says Jeanne, what cranes. Last night I dreamed only of trumpets.

These two dead cranes, says the painter going up to her, on the threshold of our apartment, says the painter, caressing the front of Jeanne’s hair, because hair too has a front and a back but it does not remotely matter.

THE OMENS CANNOT BE GOOD.

So saying, he puts his easel and paintbox under his arm and goes outside.

Perhaps I’ll even paint something he mutters into his beard.

However, he does not get further than the first bistro.

Both God and the Devil play the same key.

And that key is B-Minor, says Amedeo Modigliani, inhaling the gaze of a woman sitting at the bar.

She is pale, almost white, like a lily.

She is called Ludmilla.

She is blonde, slender, tall, thin as a northerner.

FUCK YOUR EASEL, she says.

Because, when he caught sight of that heady, white beauty, he was blinded, and he raised both his left and his right hand to his eyes in a sudden spasm, leaving his armpit open. So the easel fell and rebounded from the bistro floor dully, dead, like rotten fruit.

FUCK YOUR EASEL, she says.

Looking him straight in the eye.

And Amedeo Modigliani is looking at her feet, wild, barely captured in her exceptional shoes, he is looking at her long, waxy calves, her knees and ever upwards.

He sees her narrow hips, too narrow; her little breasts like two drops of honey, her snake-like neck and hair—MON DIEU—blonde.

I am Amedeo, the painter barely manages to utter, knocking back a cold vodka, a bit insipid, watery, as he swims in the sharp gaze of Ludmilla’s large eyes which look as though all the blue of the heavens has poured into them.

I was on my way home and just happened to turn towards Montparnasse. It’s very sad here, says Ludmilla sipping a tepid beer, in tiny, staccato gulps like a nightingale, leaving, naughtily, a garland of foam on her upper lip, so that she looks like a rough, drunken woodcutter.

Forgive me, that means you are not from round here, says Amedeo Modigliani stuck like a polyp to his glass and the bar.

No, Ludmilla shakes her head, I come from the sky.

And her words slide, rebounding from the flat surface of the bar, only to evaporate, together with the nicotine smoke somewhere towards the ceiling or somewhat higher. Forever.

Because everything that happens need not necessarily be forgotten.

SOMETHING, SOMETHING SMALL, REMAINS TO BE REMEMBERED.

And tomorrow, she smiles, I’m taking you to the cranes.

She resembles the pitiless face of death, which everyone carries on their right shoulder.

She looks like a dream in colour, like large bunches of our forebears, who did not die in vain.

Ludmilla looks like all those things that happen once in a lifetime or never. Particularly if you are a Jew and you are drunk.

And finally:

See you again, says Ludmilla in English as she goes, it is English with the heavy accent of a chronic foreigner, leaving behind a festive, cobwebby smell of rotting apples.

See you soon.

In the sky, says Ludmilla, leaving.

Her spine a little bent.

She is pale, almost white, like a lily.

She is blonde, slender, tall, thin as a northerner.

He is left alone.

There are still a few long winter hours until midnight.

Quite enough for another round of drinks.

Perhaps a bit more.

Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920) decides to get drunk.

He saw how a light flickered on and the two halves of a window opened out, somebody, made weak and thin by the height and the distance, leant suddenly far out from it and stretched his arms out even further. Who was that? A friend? A good person? Somebody who was taking part? Somebody who wanted to help? Was he alone? Was it everyone? Would anyone help? Were there objections that had been forgotten? There must have been some. The logic cannot be refuted, but someone who wants to live will not resist it. Where was the judge he’d never seen? Where was the high court he had never reached? He raised both hands and spread out all his fingers.

But the hands of one of the gentleman were laid on K’s throat, while the other pushed the knife deep into his heart and twisted it there, twice. As his eyesight failed, K saw the two gentlemen cheek by cheek, close in front of his face, watching the result.

‘Like a dog!’ he said, it was as if the shame of it should outlive him.

FRANZ KAFKA The Trial

Post Scriptum

AMEDEO MODIGLIANI DIED in the night between the twenty-fourth and twenty-fifth of January in the paupers’ Hôpital de la Charité. The day after his death, his wife, Jeanne Hébuterne, in the eighth month of pregnancy, threw herself out of a window at her parents’ house.

According to the medical report, Modigliani died by choking on his own blood.

The last thing he said before he closed his exhausted noble eyes, was:

ITALIA, CARA ITALIA.

Acknowledgments

The Outsider by Albert Camus, translated by Stuart Gilbert (Hamish Hamilton 1946) translation copyright 1946 by Stuart Gilbert. Reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd.

The Stranger by Albert Camus, translated by Stuart Gilbert, copyright 1946 and renewed 1974 by Alfred A Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc. Used by permission of Alfred A Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc.

Selected Poems by Jorge Luis Borges edited by Alexander Coleman (Allen Lane The Penguin Press 1999). Copyright © Maria Kodoma 1999. Translation copyright © Alan S Trueblood 1999. Reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd.

Selected Poems by Jorge Luis Borges, edited by Alexander Coleman. Used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group USA. Copyright © 1999 by Maria Kodoma. Translation copyright © 1990 by Alan S Trueblood.

Selected Poems by Jorge Luis Borges. Copyright © Alan S Trueblood, 1999. Reprinted by permission of Penguin Group (Canada), a Division of Pearson Canada Inc.

Explication de L’étranger by Jean-Paul Sartre © Editions Gallimard Paris 1947 and 2010.

For other quotations, Pushkin Press has made an effort to contact all copyright-holders, not always with success. Any copyright-holders of uncredited quotations in this book should write to the publisher.

Also Available from Pushkin Press

PUSHKIN PRESS

Pushkin Press was founded in 1997. Having first rediscovered European classics of the twentieth century, Pushkin now publishes novels, essays, memoirs, children’s books, and everything from timeless classics to the urgent and contemporary. Pushkin Press books, like this one, represent exciting, high-quality writing from around the world. Pushkin publishes widely acclaimed, brilliant authors such as Stefan Zweig, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Antal Szerb, Paul Morand and Hermann Hesse, as well as some of the most exciting contemporary and often prize-winning writers, including Pietro Grossi, Héctor Abad, Filippo Bologna and Andrés Neuman.

Pushkin Press publishes the world’s best stories, to be read and read again.

For more amazing stories, go to www.pushkinpress.com.

Copyright

For Bianca Sforni

Original text © Velibor Čolić

English translation © Celia Hawkesworth 2011

The Uncannily Strange and Brief Life of Amedeo Modigliani first published in French in 1995 as La Vie fantasmagoriquement brève et étrange d’Amadeo Modigliani

First published by Pushkin Press in 2011

This ebook edition published in 2012 by Pushkin Press, 71-75 Shelton Street, London WC2H 9JQ

ISBN 9781908968531

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from Pushkin Press

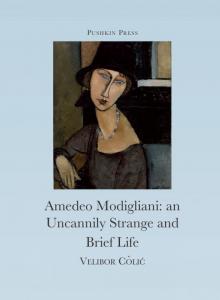

Cover Illustration Jeanne Hébuterne (au chapeau) Amedeo Modigliani

© Courtesy of Sotheby’s

www.pushkinpress.com

The Uncannily Strange and Brief Life of Amedeo Modigliani (Pushkin Collection)

The Uncannily Strange and Brief Life of Amedeo Modigliani (Pushkin Collection) The Uncannily Strange and Brief Life of Amedeo Modigliani

The Uncannily Strange and Brief Life of Amedeo Modigliani